On the Shortage of Priests

The Lobinger Proposal:

An Evolving Ministerial Priesthood for our Evolving Times?

Leo R. Ocampo

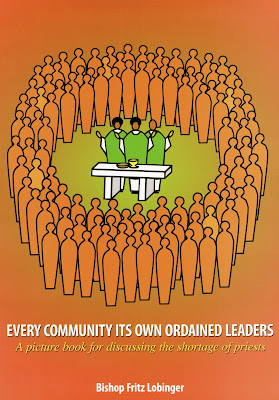

Bishop Fritz Lobinger, in his book “Every Community Its Own Ordained Leaders” tackles the shortage of priests—a very serious problem that affects many Christian communities around the world today. It is useless to pray for and aspire so as to return to the “good old times” he says, for it has now become impossible to achieve the former setup when an ample number of clergy ably managed to serve the needs of the faithful. Neither is the provisional compromise of “dry Masses” or “Sunday Celebrations in the Absence of a Priest” already being practiced here in the Philippines in remote areas that could not be ministered to weekly by the decreasing number of priests, a solution acceptable him. Instead, he floats a quite radical proposal: why not ordain lay, part-time “elders” to complement our dwindling crop of priests?

“In each of the communities, they appointed elders” (Acts 14, 23)

In the Pauline communities as was elsewhere in the early Church, he invokes, the Christian communities had leaders from their own ranks appointed by the apostles. These leaders were not like our present day priests who devote themselves full-time to ministry. Instead, they lived and worked just like ordinary people but occupied part-time liturgical and administrative positions in the service of the community. “The reason why the early Church designed the life of Christian communities in this way was not because it was at that time impossible to send to each community a presbyter from somewhere else. The reason was rather that each community should use the charisms which the Spirit had given to its own members.”

He therefore suggests a recuperation of this ancient model by ordaining a team of leaders from among the lay faithful. These part-time lay leaders will be called “elders” to distinguish them from full-time professional “priests”. They will take turns as teams presiding over the Eucharist and together as a college, they may also assume the governance of a local community. They will receive the same sacrament of ministerial priesthood but will continue in their lay state, “totally immersed in people’s lives, in working conditions and in family life.”

Unlike the priests who can be sent by the bishop to any parish in the diocese, these elders can exercise their office only in the place from which and for which they were selected. They will also remain under the tutelage of the full-time clergy who will gradually evolve from their current role as direct pastors to become formators tasked with the continuing training and oversight of these lay leaders who will be the ones to serve their own communities. The whole idea is certainly not to create a new class of pseudo-clergy or sub-clergy but to supposedly reinstate a stable, community-based ministry of lay, part-time leaders alongside the itinerant, supervisory role of the professional, full-time clergy. Hence, the appointment of elders will not be a transitional measure or as Bishop Lobinger calls it, a “stop-gap solution,” but a permanent structure wherever it is established.

According to Bishop Lobinger, certain conditions need to be satisfied before a diocese could begin to ask Rome for permission to ordain elders for at least some of its communities. First, the community being considered should have proven itself to be a “self-ministering community” for at least some years. This guarantees some readiness on the part of the community to accept leaders coming from their own ranks. This also allows the presupposition that there are not only qualified but mature persons in the community who are able to handle authority properly. Second, the majority of the priests in the diocese should be able to understand and exercise their role as formators and animators rather than direct pastors and administrators. The presence of lay leaders could threaten an insecure clergy and potentially cause tension and instability where “the solution of one big problem will create another big one.” Third, the principle of ongoing and unending formation must be agreed upon by all. This not only assures that the lay leaders are properly trained and regularly updated but also guards against lay leaders overstepping and abusing their authority. Finally, the bishop and the diocese should be fully and unanimously convinced about this decision. Such a revolutionary development will obviously meet many challenges, which will require the commitment and cooperation of all, if it is it be carried on to fruition. Hence, he does not insist that the entire Church or even an entire diocese implement it uniformly but instead suggests that it be done, one parish and one diocese at a time as circumstances indicate.

Some questions about the proposal

Bishop Lobinger’s proposal does present a cogent and workable, even if radical solution to the shortage of priests in the Church. Certainly commendable is his positive estimation of the capacity of communities to govern themselves and the ability of the clergy to reinvent themselves to adapt to a changing context. We need to ask however whether such a radical step is necessary when already in the Church we can refine the present hierarchical structure to make his model work without creating new ministries loosely rooted in tradition.

Are we not making of our present body of presbyters—that term precisely meaning “elder” (presbuteroi) in Greek, a pseudo-episcopal or sub-episcopal structure by making them function as inter-parochial overseers (episkopoi) rather than shepherds of the local community working with and under the bishop who in the present structure already functions as overseer? His treatment on what the bishop’s role would be in this setup is rather vague and cursory. Besides, it is not as if the office of lay elders in the early Christian communities vanished and their function was replaced by the invention of full-time priests. Rather, the priesthood we know now is the product of the historical evolution of that original ministry.

Moreover, is it necessary to ordain these lay elders to the ministerial priesthood? More importantly, would their ordination as such be in line with Tradition? Even in the early Church, as we find in the Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus, there was already a clear distinction which developed between ordained ministry conferred by keirotonia or the laying on of hands to signify the handing over of authority and lay ministry confirmed by katastasis or praying over these lay ministers in view of their exercise of special roles in the community. Would his application therefore of “the same sacrament of ordination” on these lay leaders, even if it were to be exercised in a different form, be not an unwarranted and discordant break with the organic development of tradition? Would it not suffice to reinforce and maximize already existing structures such as Parish Pastoral Councils and Sub-Parish Councils and delegate more and more to these lay, but non-ordained leaders the more practical and administrative functions of our priests such as managing the finances and handling the temporal affairs of the parish so our ordained ministers can focus full-time on presiding at the Eucharist, administering the other sacraments and other spiritual concerns?

On the more practical side, the motley application of his proposal among dioceses and parishes may create more confusion and division among our people than it is possible to contain. Even if the challenge is sublime of inviting everyone to a new way of understanding and doing ministry, one is seriously led to doubt whether this is the best way to proceed, given the incalculable risks that come with his prospect. He himself identified a number of alarming scenarios, especially of the community rejecting these new elders. Even if safeguards such as the criteria he enumerated can be put in place and these “temptations” are possible to overcome, they still pose severe objections to the feasibility and desirability of this project. There is no clear guarantee that the paradigm shift would be complete before our congregations begin a mass exodus.

Towards a new way of being Church

Lay empowerment is undoubtedly the way to go and abundant signs of hope can already be seen in their increased participation in the life and mission of the Church especially since Vatican II. In many parishes, they have already taken over, with much benefit, many functions both liturgical and otherwise that were the exclusive domain of the clergy before the Council. Surely, the Holy Spirit continues to inspire charisms until today with undiminished splendor and richness as manifested in its variety and diversity of expressions especially among the lay faithful who have shown themselves able to serve the Church as much as ordained people can. It is not as if ordination gave a person more authority and greater mission in the Church. But while our lay people do not need ordination to the priesthood to give them the power to serve, to pray and to lead that the grace of baptism already affords them, to ordain them still may not be such a bad idea.

Statistical trends affirm that the priestly shortage is a problem that is bound to linger and even worsen. Even while more and more of the clergy’s current tasks are already being passed on to lay hands, many of our altars still remain empty and they will probably remain so, any amount of lay empowerment or reinforcement of katastasis notwithstanding. This is the core of Lobinger’s problem that we can never gloss without reconsidering his proposal, in all its radicalism, unless of course we can offer a more acceptable yet equally potent solution.

We ask then whether the lay status of these qualified community leaders in fact disqualifies them from ordination to the ministerial priesthood? Is the present structure of ministerial priesthood we have something of immutable, inviolable divine institution that we do not have the right to adapt it even in the face of such a need heretofore unknown by the Church? History seems to indicate otherwise.

From the earliest times, ministry in the Church went along with the changing needs of the community. The apostles themselves felt free to institute and did in fact create a new ministry—that of deacons—to assist them in addressing the emerging needs of their time. We can also conjecture from reliable texts that ministries in the early Church were not always uniformly organized but that its practice partly differed among the Christian communities. It was not until the Letters of Ignatius of Antioch written in the late second century that we have an unequivocal witness of the tripartite structure that exists today. Before the development of the monarchic episcopate, the bishops shared administrative and spiritual functions with the deacons and/or presbyters in the manner that would best serve the needs of the community in that specific time. The bishops of Rome for example used to preach and preside personally at every liturgical celebration. Later on, with the establishment of parishes in the suburbs and countryside, they would progressively delegate these tasks to the presbyters whose office will now acquire a more priestly and liturgical function. In short, it was not until much later that roles in the ministerial priesthood, both administrative and liturgical, would be defined and fixed in the form we know today.

Also, ministry in the early Church did not necessarily remove people from their “lay” lifestyles even if inevitably, those ordained became distinguished more and more from the rest of the faithful primarily because of their function and not due to their separation. Saint Paul for example, continued to practice his tent-making profession alongside his vigorously unparalleled but not even full-time proclamation of the Gospel. In his Letter to Timothy, he considered the ability of an episkopos to manage his own household and children as indicative of his capacity to shepherd the community. A considerable number of the men we now revere as fathers of the Church, such as Hilary of Poitiers and Gregory of Nyssa, were also fathers of families. It was only later on, mainly because of an increasingly negative view of sexuality and also due to certain abuses in the administration of the material goods of the Church that celibacy gradually became favored among clergy. Thus the number of married presbyters who continued with live lay lifestyles dwindled until that form of ministry disappeared in the Latin Church when celibacy was established as a clerical discipline in the twelfth century. But while celibacy has its indisputable advantages and spiritual value, it is also undeniable that we have suffered much from the loss of married clergy.

We therefore find the proposal of Lobinger not that radical after all, if only we are conscious of our history, which offers a spectrum of possibilities far wider than our present perspective. An ordained body of part-time priests who will continue to live lay lifestyles while rendering service, both liturgical and otherwise, to their own community is not an impossible or unacceptable scenario. This we may confidently do, not only in view of the pressing need we have today and as a temporary measure. But having recovered a more positive appreciation of sexuality and family life, and with canonical structures already in place to safeguard the temporal goods of the Church—we could now allow not only for the reemergence but even the permanence of such a form of ordained ministry.

New wineskins for new wine

Bishop Lobinger’s proposal may yet seem too far ahead and inopportune today. Nonetheless, in tackling the problem of clergy shortage, he verily succeeded in leading us away from stopgap measures, or that passive even if prayerful nostalgia for the previous setup, to a possible solution which, upon serious reconsideration, turns out to be not a totally impossible or unacceptable one.

Our evolving times certainly call for a new way of living, serving and being, not only as clergy or laity, but also as Church. Gone forever, and gratefully so, are the days when we simply depended on the clergy to run our parishes for us and in fact even our own spiritual lives. Indeed, a most happy part of our modern ethos is its emphasis on shared responsibility and communal involvement, which unfortunately, has yet to permeate—truly and fully—our ecclesial life. For even though we may have already allowed the laity more and more involvement and responsibility in the Church, have we really considered them as partners radically equal to the clergy by virtue of our common baptism even if at the same time they are subordinate with respect to the hierarchical structure of the Church?

After all, there are many functions of priests that lay leaders, fully immersed in ordinary life and well-versed in mundane affairs, are able to perform in a much better way than professional priests can. Further empowered by ordination, which invests more authority in them, we can only imagine their potential for service. More importantly, they will bring as presiders a unique contribution that cannot be matched by professional priests. Although their preaching may be less theological, they will be able to connect more closely to the context of our people whose lives and struggles they live. Their voice in the liturgy will thus express more deeply and sincerely, because more closely as well, the sighs and groanings arising from the hearts of people with whom they are one. But far from competing with the full-time priesthood they will be complementing it, cooperating with it, contributing to it, for the better service of the community that continues to receive different yet mutually enriching gifts from the same Spirit for the good of all.

“A new vision of the Church is at stake,” he says with courage and hope of no less than prophetic proportions. Before the Lobinger proposal can be implemented, the clergy would first have to rethink their notions of ecclesial authority and pastoral care. The community will need to adopt a new concept of priestly life and ministry as well as of lay involvement and responsibility. The present structure of the ministerial priesthood and its underlying beliefs and value systems will have to be shaken and reinvented, requiring no less than a complete paradigm shift in all stakeholders. And like all paradigm shifts, it will not be quick or painless, but it will almost surely pledge a future full of possibilities.

New wine, even if this particular wine is really not that new, will tend to burst old, dried-up wineskins. Yet we need not be afraid of new wine. Instead, we need to prepare new and supple wineskins ready to receive it. So we thank the bishop for pointing us towards a promising direction. Now we may begin working on new wineskins to receive the wine of a new priesthood for our thirsting people. †

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home